Cute Code is Not Helpful

I think we did it to ourselves. Getting entry-level engineering jobs has become an arms race of impossible LeetCode riddles and challenges that have little to do with the actual day-to-day work. It might surprise some new grads to learn that they don’t use advanced BFS techniques every day while maintaining an analytics dashboard for subscriber data.

A natural consequence of this LeetCode-driven culture is that the rising generation of engineers are extremely strong in algorithmic problem-solving, and many of these engineers have a tendency toward “cute” code. You know the type: code that’s not easy to read, written in the name of being clever or shaving a few lines off a solution.

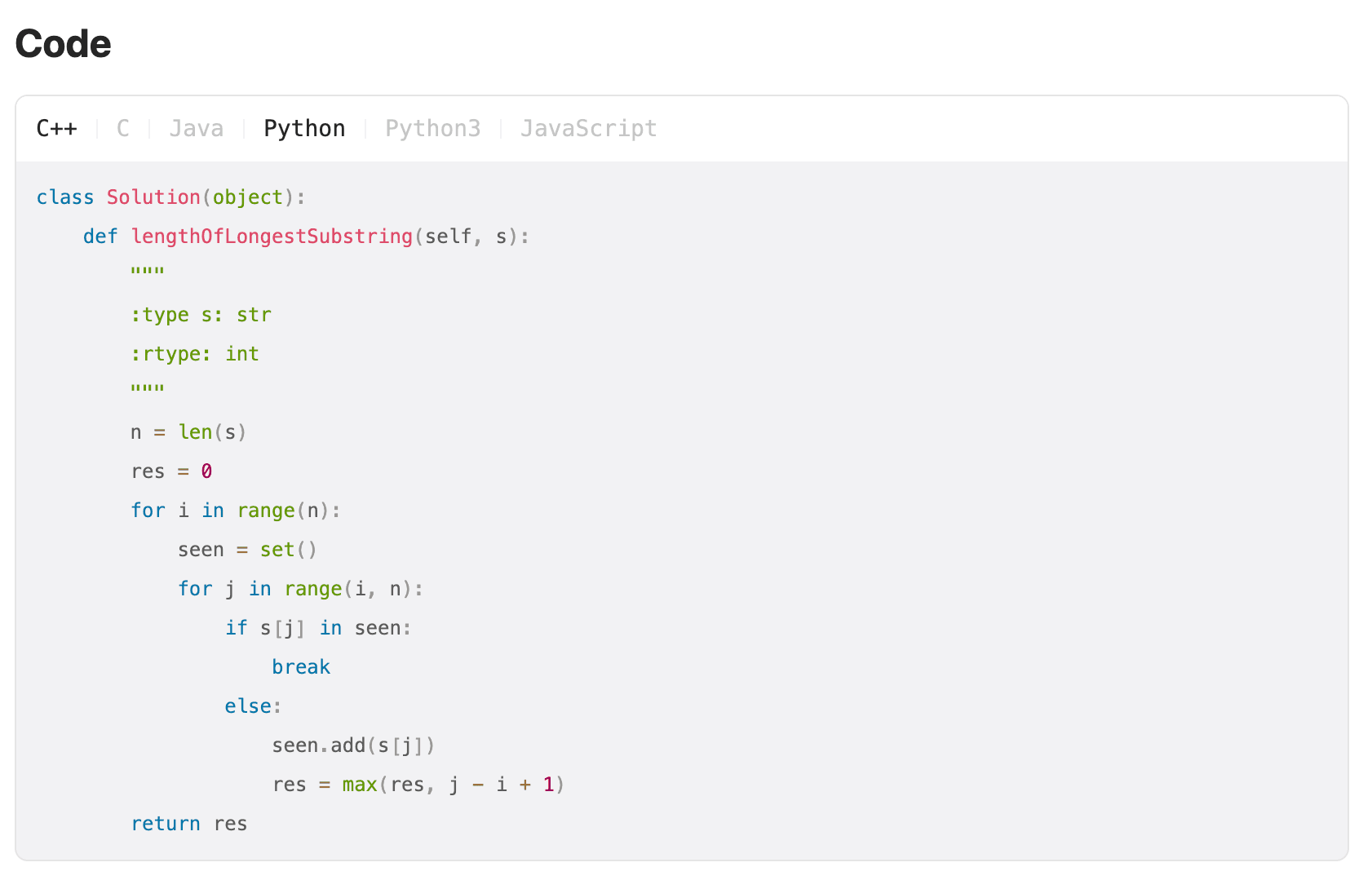

Let’s do a quick deep dive. Take the LeetCode problem Longest Substring Without Repeating Characters, a fairly well-known problem. There are tons of solutions posted online. Like this highly upvoted one from the discussion board.

There's nothing wrong with this solution. But it’s a bit cute. No inline comments, generic variable names, no method docstring, no explicit argument typing—nothing to make it easy for future engineers to pick up where you left off. If you have some programming experience, you could probably understand it in a few minutes given the context of the problem.

But imagine encountering that same code in the wild, without any context: the commit date is 12 years ago, and the engineer who wrote it now owns a weed dispensary in Seattle. Specs and documentation? Forget about it. Unit tests? I've got news for you, kid, they don't exist. What does this code even do? Can you modify its behavior with any confidence? Do you even need it at all?

Suddenly, this cute code becomes a bit of a stability risk. Yes, you could probably spend some time reading over the code and figure out what this was doing and why. But that takes precious time, and unnecessary time at that. Plus, there's always the chance that you're wrong.

This is optional suffering. Compare the solution above with this version that does the exact same thing using the same algorithmic runtime, but with an emphasis on clarity and long-term maintainability.

def get_longest_unique_substring(s: str) -> int:

"""

Find the length of the longest substring (case-insensitive) without

repeating characters.

Args:

s (str): The input string

Returns:

int: Length of the longest substring with all unique characters.

"""

# Loop over each position in the string as the starting index and try

# to find the longest unique-character substring starting from there

max_length: int = 0

for start_index in range(len(s)):

# Track visited characters in the current substring

seen = set()

# Extend the substring from start_index to the right

for end_index in range(start_index, len(s)):

char = s[end_index].lower()

# If the character is already visited in this substring, then exit

if char in seen:

break

# Mark the character as visited, and update the max length

seen.add(char)

max_length = max(max_length, end_index - start_index + 1)

return max_length

Editor's Note: Yes, I know these solutions are not the optimal algorithmic runtime, but the point still stands.

So why does all this matter? One survey reported that engineers spend about 40% of their time dealing with maintenance and tech debt, with an average of 3.8 hours per week spent simply debugging legacy “bad” code.

Cute code isn’t the lone gunman responsible for technical debt and maintenance problems. But once we start talking about 10% of a developer’s time being spent just trying to decipher old code, it becomes clear that this is a significant problem space. Some reports suggest that the size of the tech debt "industry" reaches into the trillions of dollars, so we’re talking about more than tabs versus spaces here.

And I’m not the only one who thinks this way:

“When asked, I would give people my opinion that maintainable code is more important than clever code,” he said. “If I encountered clever code that was particularly cryptic, and I had to do some maintenance on it, I would probably rewrite it. So I led by example, and also by talking to other people.” —Guido van Rossum, creator of Python

The next time you’re writing code, just think about the engineer five years from now who’s going to read it with zero context. Call it the golden rule of programming: write code unto others as you would want it written unto you. Your coworkers, and your company's top-line productivity metrics (if you're into that kind of thing), will thank you.

The team at /dev/null digest is dedicated to offering lighthearted commentary and insights into the world of software development. Have opinions to share? Want to write your own articles? We’re always accepting new submissions, so feel free to contact us.

Related Posts

By posting you agree to our site's terms and conditions , ensuring that we can create a positive and respectful community experience for everyone.